Basic Java exception handling

- Errors and exceptions

- Throwing and the throws declaration

- Catching exceptions

- Cleaning up using try-with-resources

- Cleaning up using finally

- Rethrowing and chaining

- Turning checked exceptions into unchecked exceptions

- Resources

Almost every program will need some kind of error handling for when things go wrong, either because of incorrect code or because of things that the code has no control over (e.g., network errors). This post explains the tools Java provides you for handling errors.

Errors and exceptions

When a method encounters a situation that prevents it from doing what it should do, it needs some way to make the caller of the method aware of this. One way of doing this is to return an error code if something went wrong. If the caller gets back an error code, it can then respond accordingly, possibly propagating the error to its own caller with an error code. A big drawback of this is that the caller must remember to check for error codes and then do something with them.

As an alternative to this, Java and a lot of other modern languages support the concept of exception handling. Here, a method can throw an exception indicating that something is wrong. These exceptions automatically bubble up the call chain until they are handled (or, if they are not handled, they end up terminating the current thread). Typically, they include a stack trace, indicating where the exception occurred in the code and what the call chain looked like at the time.

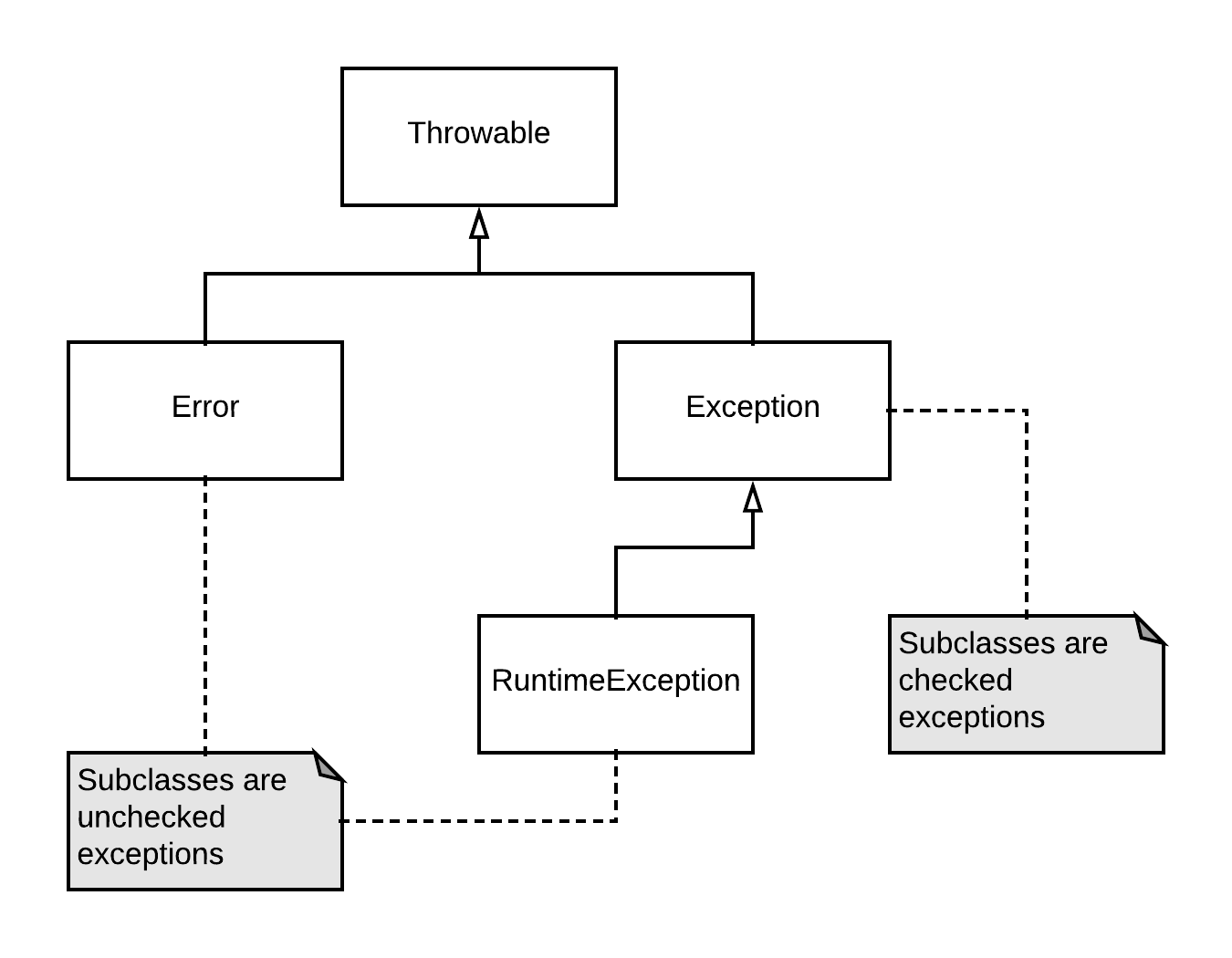

In Java, there are several kinds of exceptions. The following image describes what the general hierarchy of exception classes in Java looks like.

All exceptions are direct or indirect subclasses of the Throwable class. Subclasses of Error are exceptions defined by the Java language that are thrown when something really bad happens that the code can normally not recover from by itself. An example of this is OutOfMemoryError, which occurs when Java is unable to allocate space to an object because there is no more memory available and garbage collection does not help. If you run into that one, the best you can generally do is exit the program.

These Error exceptions are all unchecked. This means that the Java compiler does not check how we deal with these exceptions. This is different for checked exceptions: if your code can possibly throw a checked exception, the Java compiler requires you to either catch the exception or use a throws declaration to indicate that your code can throw the exception.

User-defined exceptions are all subclasses of the Exception class. Exception classes that directly derive from Exception are checked exceptions. Exception classes that derive from RuntimeException are unchecked exceptions. The name RuntimeException could be a bit confusing, as all exceptions occur at runtime. The idea is that, unlike checked exceptions, the way you handle unchecked exceptions is not checked at compile time (hence the “runtime”).

Throwing and the throws declaration

Throwing an exception is as easy as obtaining an instance of the exception and throwing it. An example is the following code.

public static boolean isNumberBetween(

int number, int lower, int upper

) {

if (lower > upper) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"Lower bound cannot be higher than upper bound");

}

// ...

}

In this case, we were throwing an IllegalArgumentException, which is unchecked. This means we do not need to declare (using a throws declaration) that the method can throw an exception of that type, although we can choose to declare it explicitly. The above code is an example of using unchecked exceptions to indicate programming errors: it never makes sense for the caller of this method to specify a lower bound that is higher than the upper bound.

If the code in a method can throw a checked exception, your code will not compile until you declare it. One example of a checked exception is IOException, which you will encounter a lot when working with files.

// error: Unhandled exception type IOException

public void write(String text, String filePath) {

// potentially throws IOException

Files.write(Paths.get(filePath), text.getBytes());

}

We can fix the compiler error by either catching the IOException or declaring it using a throws clause.

public void write(String text, String filePath)

throws IOException {

Files.write(Paths.get(filePath), text.getBytes());

}

This is a way for the compiler to remind us that there is a possibility for failures and that we will have to deal with those failures at some point in the code.

If you override a method, you cannot throw more checked exceptions than the original throws clause specifies. Otherwise, you would break the contract of the method. This also means that, if a method does not have a throws clause, any method overriding it cannot throw any checked exceptions. Note that you can perfectly override a method declaring checked exceptions with a method not throwing any exceptions at all.

In general, it is always allowed to include checked exceptions in your throws clause that you don’t actually use. This may be useful in a superclass that needs to allow subclasses to throw these checked exceptions.

Catching exceptions

In order to handle an exception, you first need to catch it. Catching an exception allows your code to detect when the exception occurs and prevents the exception from bubbling up further through the call chain (although you can still trigger this yourself, see later).

Catching an exception happens in a try-catch block. In its simplest form, it looks like this:

try {

// code potentially throwing exception

} catch (TheExceptionClass ex) {

// code handling the exception

}

You can also have multiple catch statements, catching exceptions of different exception classes. They are evaluated top to bottom, so put more specific exception classes first. It is also possible to have a handler that can handle several exception classes.

try {

// code potentially throwing exception

} catch (ExceptionClass1 ex) {

// code handling the exception

} catch (ExceptionClass2 | ExceptionClass3 ex) {

// code handling the exception

}

Cleaning up using try-with-resources

One challenge regarding exception handling is the cleanup of resources. For example, if you have opened a file and an exception occurs while doing something with it, you should make sure that the file is still being closed at some point.

In Java, one way to solve this is called a try-with-resources statement. In this form of try statement, you can specify resources that should be closed automatically. The fact that a resource can be closed automatically is indicated by the fact that it implements the AutoCloseable interface. As an example, look at the following code.

public void write(ArrayList<String> lines)

throws FileNotFoundException {

try(PrintWriter out = new PrintWriter("output.txt")) {

for (String line: lines) {

this.possiblyGenerateException(line);

out.println(line);

}

}

}

When the code exits the try block, either because we finished processing the lines or an exception was thrown inside, the PrintWriter will be closed automatically. It is also possible to provide multiple resources to a try-with-resources statement. In that case, the order in which they are closed is the reverse of the order in which they were provided.

A try-with-resources statement can also have catch clauses catching any exceptions occurring in the statement.

It is possible that closing an AutoCloseable throws an exception itself. If that happens after normal execution of the try block, that exception is passed to the caller. However, if an exception happens inside the try block, that exception will be passed to the caller and any exceptions generated by subsequently closing the resources will be attached as suppressed exceptions on that exception. When catching the exception that happened in the try block (the primary exception), you can access those suppressed exceptions by invoking the getSuppressed() method on the caught exception.

public class ThrowsOnClose implements AutoCloseable {

@Override

public void close() {

throw new IllegalStateException("Closing");

}

}

try (ThrowsOnClose throwsOnClose = new ThrowsOnClose()) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Inside try");

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage()); // Inside try

for (Throwable suppressed: e.getSuppressed()) {

System.out.println(suppressed.getMessage()); // Closing

}

}

Cleaning up using finally

An alternative to the try-with-resources statement is the finally clause. This is especially useful if you need to clean up something that is not an AutoCloseable. After the try block and potential catch blocks, you add a finally block which will run after the rest of the try-catch statement has finished.

You should avoid throwing exceptions in the finally block. If the code in the try block throws an exception and then the finally block throws an exception, the caller of the method will only see the exception from the finally block. The suppression mechanism we saw above only works with try-with-resources statements. For example, a caller of the method below will only see the IllegalStateException:

public void test() {

try {

throw new IllegalArgumentException();

} finally {

throw new IllegalStateException();

}

}

Rethrowing and chaining

It is possible that your code wants to do something with an exception (for example, log it) but still wants the exception to bubble up further through the call chain. In this case, you can simple catch the exception, do what you want to do with it, and then just throw the exception object that you caught.

It is also possible catch a certain exception and throw a new exception instead. In this case, the original exception is typically included as the cause for the new exception. This is called the chaining of exceptions. As an example, the following code catches a SQLException but returns it to the caller as the cause for a custom exception which makes more sense to the caller.

try {

// set foreign key to parent in database

} catch (SQLException ex) {

throw new ParentNotFoundException(ex);

}

When the caller catches the ParentNotFoundException, it can find the original exception using the getCause() method.

In this case, ParentNotFoundException has a constructor which allows passing the cause (this is considered good practice). If an exception class does not allow that, the cause for the exception can be set through the initCause() method.

try {

// set foreign key to parent in database

} catch (SQLException ex) {

Throwable wrapped = new ParentNotFoundException();

wrapped.initCause(ex);

throw wrapped;

}

Turning checked exceptions into unchecked exceptions

In some cases, you may find yourself getting a checked exception which you want to pass up the method chain as an unchecked exception (for example because you are overriding a method without a throws declaration allowing the checked exception).

One way of doing is the chaining of exceptions, which we saw above. It is perfectly possible to catch a checked exception, set that exception as the cause for a new unchecked exception and then throw the unchecked exception to the caller. In the above examples, ParentNotFoundException could have been an unchecked exception. This is the recommended way of turning checked exceptions into unchecked exceptions.

There also exist sneaky approaches that trick the Java compiler into ignoring checked exceptions. An example is the following implementation which I took from Core Java SE 9 for the Impatient (see resources below).

public class Exceptions {

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

private static <T extends Throwable>

void throwAs(Throwable e) throws T {

throw (T) e; // erased to (Throwable) e

}

public static <V> V doWork(Callable<V> c) {

try {

return c.call();

} catch (Throwable ex) {

Exceptions.<RuntimeException>throwAs(ex);

return null;

}

}

}

Now, any checked exceptions thrown inside the doWork method are ignored by the compiler.

public static void test() {

// error: unhandled FileNotFoundException

new PrintWriter("output.txt");

// ok

Exceptions.doWork(() ->

new PrintWriter("output.txt"));

}

Although this is a pretty cool trick, it is not generally applicable in practice. Not only would it be confusing to catch an IOException from a method that doesn’t declare it, but the compiler does not even allow you to do it.

public static void invokeTest() {

try {

test();

} catch (IOException ex) {

// error: unreachable catch block

}

}

public static void test() {

Exceptions.doWork(() ->

new PrintWriter("output.txt"));

}

There are some limited use cases where it could make sense to use this trick (although they are not necessarily considered good practice). The first one is if you are creating a Runnable that can throw a checked exception in its run() method (which does not declare any checked exceptions). You can define custom error handling behavior for the thread (for both checked and unchecked exceptions) in the thread’s uncaught exception handler.

public class TestRunnable implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

Exceptions.doWork(()

-> new PrintWriter("unwritableFile"));

}

}

Thread thread = new Thread(new TestRunnable());

thread.setUncaughtExceptionHandler(new UncaughtExceptionHandler() {

@Override

public void uncaughtException(Thread t, Throwable e) {

if (e instanceof IOException) {

System.out.println("Caught IOException");

}

}

});

thread.start(); // Caught IOException

Another case where it could make sense to use this method is when dealing with “impossible” exceptions. There are some methods in the standard library with a throws clause declaring checked exceptions, although there are some sets of arguments which are guaranteed to never throw an exception. If you know that you are passing such a set of arguments, you could use this trick to stop the compiler from bothering you about this impossible exception.

Resources

- Core Java SE 9 for the Impatient (book by Cay S. Horstmann)

- Project Lombok @SneakyThrows (throwing checked exceptions as unchecked)