Trunk Based Development

- What is Trunk Based Development?

- Trunk Based Development advantages

- Commits and reviewing

- Trunk Based Development and Continuous Integration

- Trunk Based Development and Continuous Delivery

- Releases

- Dealing with larger changes

- Some good practices when applying Trunk Based Development

- Resources

Trunk Based Development is a source-control branching model that limits developer collaboration to a single branch, the “trunk”. This can feel quite restrictive, but it can actually help teams increase the quality of their code base and their ease of deployment. This post aims to give a high-level overview of what practicing Trunk Based Development looks like.

What is Trunk Based Development?

- Collaboration between developers happens through regular commits to a single branch, the “trunk” (ideally, several commits per developer per day)

- Developers strive to keep the code in the trunk working at all times (builds, passes tests, etc.). Every commit on the trunk should be releasable without much additional effort.

- Developers either commit directly to the trunk or commit to short-lived feature branches that are merged into the trunk after successful review

- If used, feature branches don’t last more than a few days max and only a single developer (or pair of developers) commits to a single feature branch

- Releasing happens either directly from the trunk (tagging a commit) or from release branches branched off of the trunk

Trunk Based Development advantages

Reducing distance between developers

Perhaps the biggest advantage of trunk-based development is that it limits distances between developers.

In a branching model with long-lived feature branches, one or more developers can work in separation from the rest of the team for days, weeks, or even months. Being able to work in isolation from the rest of the team can seem like a blessing. However, someday, your code will have to be integrated with the rest of the codebase. The more pain you avoided (or should I say postponed) by choosing not to adjust to changes others were making, the more pain you are saving up until the time has come to merge your feature branch.

Some people have argued that, as version control systems get better and better at merging code, we really shouldn’t be afraid of big merges anymore. What they seem to be overlooking is the following:

- There will alway be cases where source control systems cannot perform the merge automatically. These merge conflicts need to resolve manually, and this becomes more and more difficult as the scope of the merge increases.

- Even worse than this are the conflicts that your source control system does not pick up on. These conflicts are called semantic conflicts. The merge seems successful, but the code will either fail to compile, fail to run or (most dangerous case) succeed to run but produce incorrect results.

Some examples of semantic conflicts:

- I rename a method, letting my IDE help me to change its name everywhere it is used. Meanwhile, you create some new code that calls the method (by its old name). Note that this will trigger compiler errors once we merge our code (if using a statically typed language), unless there is now another method with the old name and same signature that does something else than the renamed method (more dangerous).

- There is a method that has a certain side effect. I decide to split out the side effect into a separate method, potentially because I have a new case where it is not needed. Then, I make sure to update all existing calls to the method to call the method for the side effect separately. Meanwhile, you write some new code calling the original method and expecting the side effect. The compiler doesn’t detect anything once we merge our code, we can only hope our tests will.

- I change an abstraction while you build some code on top of the original abstraction. This one will probably trigger some compiler errors once we merge (if our language is statically typed), but could require you to completely change your approach.

If developers collaborate on a single branch, these types of issues are less likely to occur because developers try to stay up to date with the trunk and analyze if any changes made by other developers affect them. And, if semantic conflicts do occur, Trunk Based Development will make sure they are detected sooner rather than later, making them much easier to solve.

Commitment to quality of code and build process

The fact that the team strives to keep the code in the trunk working at all times automatically means a dedication to the quality of code and the build process.

- There will likely be more communication regarding changes, especially if they are likely to affect other developers. Developers can also chop up changes into several commits with the sole purpose of making it more clear what they are changing and helping other developers consume and adjust to these changes.

- Dedication to working code in the trunk means that there is a high bar for code changes and typically also some kind of reviewing process. Developers are typically also more careful with their changes if they know they immediately affect the entire team.

- Keeping the code in the trunk working also means there is a strong incentive to set up a good build process that performs as many automated checks as possible to make sure the code actually does work. Developers should also run this build process locally in order to make sure their changes work before actually pushing their code.

This part also highlights a possible challenge: Trunk Based Development does require a certain level of dedication to quality from everyone in the team and the team needs to be able to self-police if necessary.

Flexibility to refactor where needed

In teams where work happens on long-lived feature branches, refactoring could turn an already challenging merge into a complete disaster. The thought of a painful merge can actually keep the team from applying the refactoring that the codebase needs. When practicing Trunk Based Development, the reduced distance between developers makes refactoring a lot easier, meaning that developers are more likely to do it when it makes sense.

Flexibility regarding releases

In principle, every commit on the trunk should be a working version of the software, very close to being releasable. This means that Trunk Based Development provides a lot of flexibility regarding when and what to release.

Commits and reviewing

Committing straight to the trunk

Especially for smaller teams, committing straight to the trunk can work. Typically, there will be some kind of review (on top of the automated build process that developers can run on their machines as well). If the team uses pair programming, a pair is often allowed to commit directly to the trunk because two pairs of eyes looked at the code. Synchronous review, where the committer calls a colleague over to check the code before actually committing, is also a possibility.

Short-lived feature branches for review

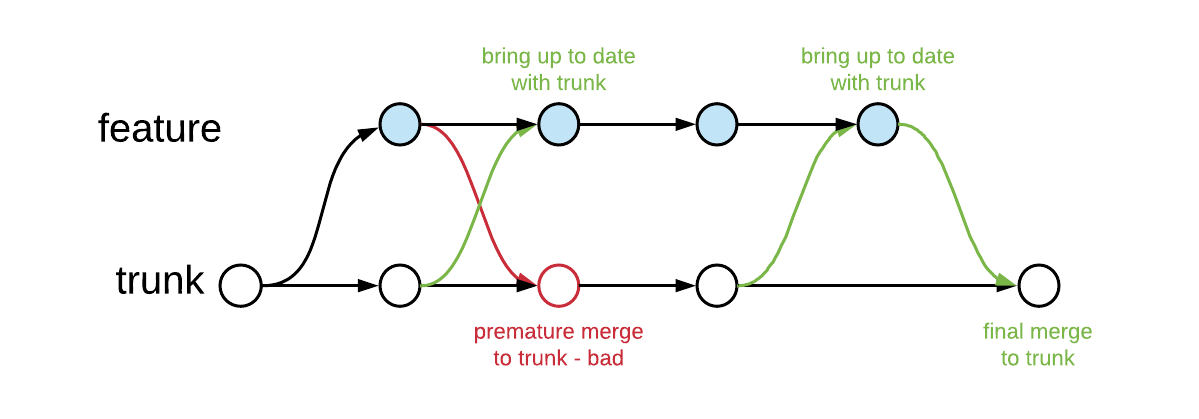

Trunk Based Development allow feature branches as a tool for code review, with some restrictions:

- Feature branches are short-lived (shorter is better, definitely not more than a few days)

- Only one developer commits to a given feature branch.

- Merging from the feature branch to trunk is also allowed once and also means the end of the feature branch

- Merging from trunk to bring the feature branch up to date with new changes is allowed anytime. It is especially recommended to bring your feature branch fully up to date with the trunk (and check that it builds) before actually merging into trunk

Pull requests (as offered by GitHub and Bitbucket) are a good way to handle this, and they make it easy to delete the branch when you merge it.

Review after the fact

As it is the team’s responsibility to keep the code in the trunk working, team members may choose to review commits that were pushed to the trunk. In case of any issues, the team can quickly coordinate on how to fix them.

Trunk Based Development and Continuous Integration

Depending on who you ask, Continuous Integration can mean two things:

- Developers very regularly integrate their changes into a single place where changes from all developers come together, making sure that they are of sufficient quality before doing so. You could argue this was the initially intended meaning of Continuous Integration, and it is more or less the same as the main premise of Trunk Based Development.

- There is some kind of process that watches the source control repository for changes and runs new commits through the build process (including tests etc.), alerting the team if the build does not pass.

The second meaning is something very useful to have if practicing Trunk Based Development. If it somehow occurs that the code in the trunk does not build, the team can take action immediately. Note that this should in principle never happen, as developers should run the same build process locally before pushing their code. This kind of automated build is also useful to have on feature branches and can be one of the deciding factors in the decision to merge. For checking commits on feature branches, it is important that the branches are sufficiently up to date with the trunk. This is especially the case right before merging.

Trunk Based Development and Continuous Delivery

Once a team has set up Continuous Integration (in every sense of the word), it can choose to move on to the next step: Continuous Delivery. This means that commits that build successfully are automatically deployed to a quality assurance or acceptance testing environment.

Continuous Deployment takes it a step further: here, commits that build successfully are actually pushed all the way to production. Not that this requires very extensive checking as part of the build process.

Releases

Branching for release

The concept of branching for release is relatively simple:

- The decision is made to release a state of the trunk

- A release branch is created, starting from the commit representing that state of the trunk

- Potentially, some very limited work happens in the release branch in order to fully make it release-ready

- The code is released and the released commit is tagged

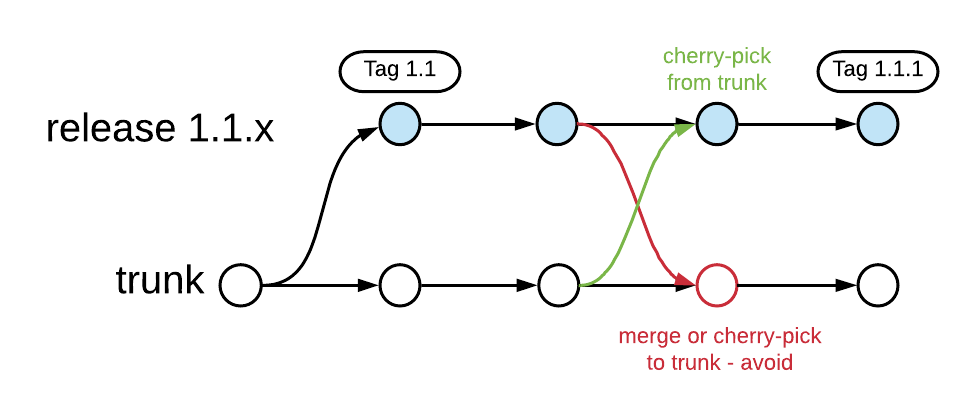

If the release contains bugs, the process is as follows:

- Fix the bugs on the trunk and cherry-pick them into the release branch, and not the other way around! This helps prevent regression bugs caused by applying a fix in a release branch but forgetting to apply the fix on the trunk as well. Exceptions are only allowed if it is really not possible to reproduce the bug on the trunk.

- The code is released and the released commit is tagged

Releasing straight from trunk

Some teams release straight from the trunk, without creating a new release branch. This is doable if commits on the trunk are really release-ready. In this case, there are often een no real version numbers. Instead, commit identifiers can be used. This approach is often seen in teams that release very often. In case of bugs in a release, these teams typically choose a fix-forward strategy where they fix the bug as soon as possible and then push a new release.

Creating a release branch only when needed

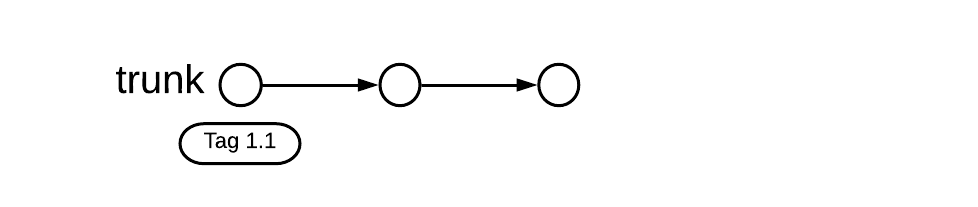

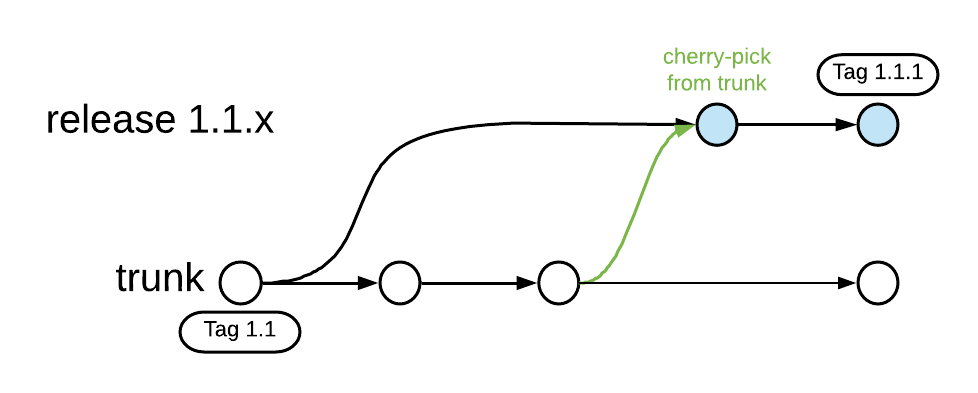

Teams following this approach release directly from trunk, tagging the commit with a release number. If a bug exists in the release, a release branch is retroactively created from that commit (modern source control systems allow this) and fixes can be cherry-picked into that branch.

This is what this looks like when releasing version 1.1 directly from the trunk:

Then, if a fix is needed for the release, a branch is created retroactively from the release commit.

Dealing with larger changes

In principle, every commit in the trunk should be releasable. When introducing new features or performing other large changes, it is often not feasible to make all of the changes in a single commit of reasonable size (and smaller commits are seen as better). Fortunately, there are some strategies that can be used to spread out changes while keeping each commit potentially releasable. There will be some follow-up posts where these are discussed in more detail.

Feature flags

Feature flags (also known as feature toggles) are a mechanism to alter system behavior without changing code. They can be thought of as light switches that switch on or switch off some parts of the system. As long as a new feature that is being built is not release ready yet, the feature can be hidden behind a feature flag in a configuration file or command line parameter. Inside the code, there is then some logic that looks at the flag and decides which behavior to enable. This makes it possible to ship the product containing the code for the new feature without the new feature actually being enabled in production. Meanwhile, the development team can enable the feature for testing purposes by switching on the feature flag.

It is also possible to use feature flags to make an application behave differently for different users, which can be helpful for A/B-testing.

Note that feature flags do introduce some complexity in the codebase. It can also be challenging to ensure that all relevant flag combinations have been tested properly. If possible, prevent the need for feature flags by designing features in such a way that even the earliest work on a feature either already has some value or simply does not change the experience of the user.

Branch by Abstraction

Branch by Abstraction is useful if the team needs to replace a certain component of the system, but this needs to be spread out over multiple commits.

Basically, this is how it works:

- Write a layer of indirection on top of the component you need to replace

- Make clients call the indirection instead of the original component

- Now, use the layer of indirection to switch over to the new component as it is being built. The new layer of indirection could already forward some calls to the new component, or there could be a toggle indicating which component implementation to use.

- Once the new component is fully built and the layer of indirection doesn’t call the old component anymore, get rid of the old component

- Get rid of the layer of indirection

Application strangulation

Application strangulation is very similar to Branch by Abstraction, but it works at the level of different applications or processes. An example is the migration of an API to a completely different programming language. You could then put a reverse proxy in front of the old API and have it start forwarding some calls to the new API as that one is being built. Once the new API is fully operational and all calls are routed to it, you can then get rid of the old API and potentially also the reverse proxy.

Some good practices when applying Trunk Based Development

- Quick reviews: Developers try to get their code reviewed as soon as possible.

- Chasing HEAD: Developers try to stay up to date with changes to the trunk.

- Shared nothing: Developers run the build locally before pushing their code, typically including integration and functional tests talking to real databases etc. This means individual developers must be able to run the application and all its dependencies locally, without depending on resources shared with others.

- Facilitating commits: Developers sometimes chop up their work into multiple smaller commits in order to make their changes easier for their teammates to adjust to. For example, when building a feature entails introducing a new dependency, this dependency could be introduced separately through a new commit that the developer explicitly notifies the team of.

- Thin Vertical Slices: Stories or tasks from the backlog can ideally be implemented completely by a single developer or pair of developers in a short amount of time and small number of commits. They cut across the whole stack and they do not need to be passed around between developers with specialized knowledge in order to get completed.