SOLID principles

- Single responsibility principle

- Open–closed principle

- Liskov substitution principle

- Interface segregation principle

- Dependency inversion principle

- Resources

The SOLID principles are five software design principles that aim to make the code more clear, offer more flexibility and help with maintainability. Although they were originally aimed at object-oriented design, more specifically the design of classes, the general ideas behind most of them are universal and can also be applied to other paradigms like functional programming.

Single responsibility principle

A class should have only one reason to change

This principle essentially means that each class (or module, or function, or …) should be responsible for a single well-defined part of the functionality of the program, and that part of the functionality should be completely encapsulated within the class (or module, or function, or …). The basic idea behind the principle is closely related to the concept of “separation of concerns”. Each part of the software should do one well-defined thing. This idea applies practically everywhere in software development.

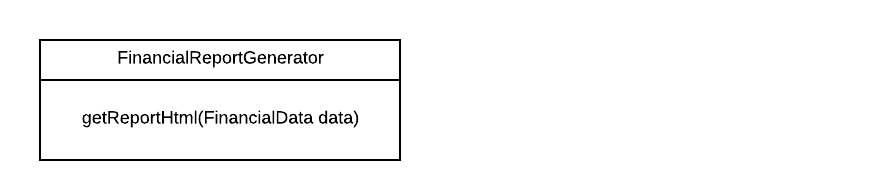

A classic example of the single responsibility principle is creating and outputting a financial report. Let’s say we first have an implementation which mixes the code for generating the contents of the report and the code that determines what the report will look like. This is a violation of the single responsibility principle.

Here, there is a single method getReportHtml that determines both the contents of the report (what data to include) and the look of the report (colors, alignment, margins, …). This means that the class needs to change if the data to include in a report changes, but it also needs to change if the report needs to look different visually. And, depending on the extent to which the code for the class’ two responsibilities is intertwined, performing changes related to one responsibility could easily break the class’ behavior with regards to the other responsibility.

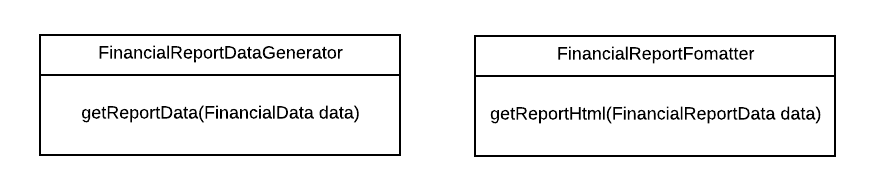

Now, let’s have a look at a version where the two responsibilities are separated.

In this version, we have one class that is responsible for determining the actual data that will be shown on the report, while another class is responsible for actually formatting that data as HTML.

Separating the responsibilities into classes encapsulating them has a number of benefits:

- When you need to change something, either the data to include on a report or the way it is formatted, you immediately know where to go.

- There is no chance of unintentionally messing with the formatting code when you are making changes to the data to include, and vice versa.

- Separating responsibilities into separate classes helps us to apply some of the other principles, as we will see later on.

Open–closed principle

Classes should be open to extension and closed to modification

This principle basically states that we should allow for extending the behavior of a part of the software (class, module, function, …) without having to touch the source code that part. One way to do this is inheritance. We could take a base class, extend it, and then override some of its behavior, potentially referring to the original implementation where appropriate. We could extend concrete classes, but we could also have abstract classes (with some abstract methods) which are specifically designed to allow subclasses to determine how certain things should happen. Even more abstract than abstract classes are interfaces; we can use those as well to allow us to change the behavior of a part of the system while minimizing the amount of existing code we need to change.

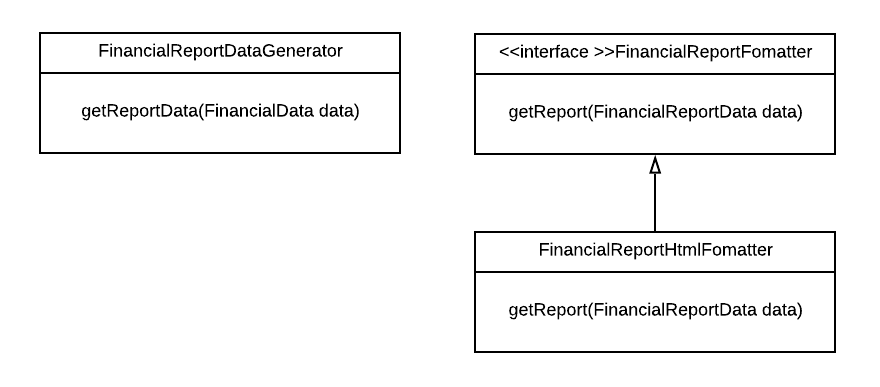

For example, we could make FinancialReportFormatter an abstract class or even an interface and then provide a concrete class FinancialReportHtmlFormatter that that formats the report as HTML.

Using this setup, it is easy to add the capability for generating reports in PDF, in black and white, with page numbers, etc. We just need to create a new implementation for the FinancialReportFormatter interface that takes care of this. There is no need for changing any existing code in the classes in our diagram.

Note that “plain” inheritance, extending a base class and then overriding some of its methods as needed, is not always feasible. For example, it is possible that the class forbids subclassing (e.g. by making it final in Java). In that case, delegation can be the answer. If the public interface of the class you want to extend is abstracted into an interface, then you can create a new class implementing that interface. That new class can then hold a reference to a “base object” of the class you wanted to extend, delegating to that base object where needed.

Delegation can also be useful if you don’t have control over instantiation. Let’s say you have a class that you want to extend. The class allows subclassing, but your problem is that the objects necessary to instantiate the class are encapsulated in some subsystem. You can request instances of the class from that subsystem, but there is no way to make the subsystem create instances of your own subclass directly. What you can do in this case is to create instances of your subclass that delegate to instances of the base class that you obtain from the subsystem.

Liskov substitution principle

An instance of a class can be substituted with an instance of any of its subclasses

Or, in other words: code that expects to get an object of a certain class A shouldn’t need to care if it receives an instance of a subclass B of A instead.

A well-known example of a violation of this principle is the square/rectangle problem.

Let’s say we have a class Rectangle with methods setHeight(), setWidth() and getArea(). Now, we want to to have a class Square as well. Since math tells us that every square is also a rectangle, we decide to make Square inherit from Rectangle. We then override the setHeight() and setWidth() methods so they each set both the height and the width (otherwise, our square wouldn’t be a square!).

This becomes problematic if we have code like this:

Rectangle rect = codeThatActuallyReturnsASquare();

rect.setHeight(5);

rect.setWidth(2);

assert(rect.getArea() == 10);

This means that we have an issue with our inheritance hierarchy, as the Square class is not a proper substitute for Rectangle. An example of an inheritance hierarchy without this problem would be a ColoredRectangle that inherits from Rectangle and allows setting and getting the rectangle’s color without influencing the behavior of the other methods. Or, we could have a ReplicatedRectangle that extends Rectangle’s methods so they forward any changes in the rectangle’s height and width over the network. As long as the behavior added or changed by the subclass doesn’t break the contract of the superclass, we are fine.

Interface segregation principle

Classes should present client-specific interfaces

This principle is particularly relevant when working with languages that require classes to be recompiled and redeployed if something they depend on changes.

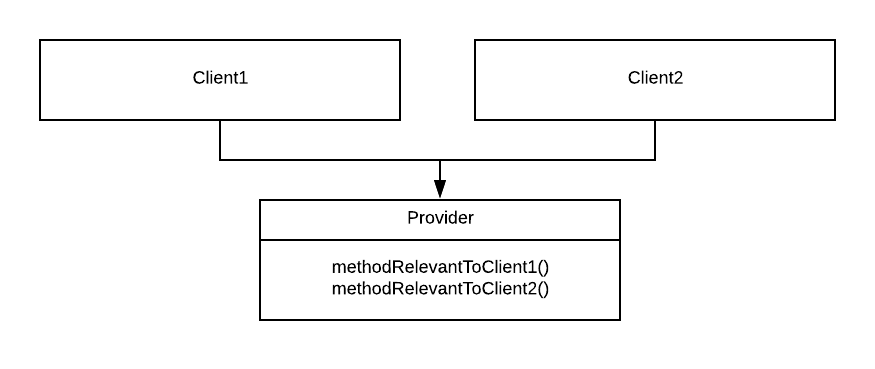

Let’s assume that we have a class Provider that has two methods. There are two clients using the class, and each of the clients only uses one of the methods.

Now, what happens if I rename the second method (which is only relevant to Client2)? If I am working in a language that requires classes to be recompiled and redeployed if something they depend on changes, I need to recompile and redeploy Client1 as well, even though nothing relevant to Client1 has changed.

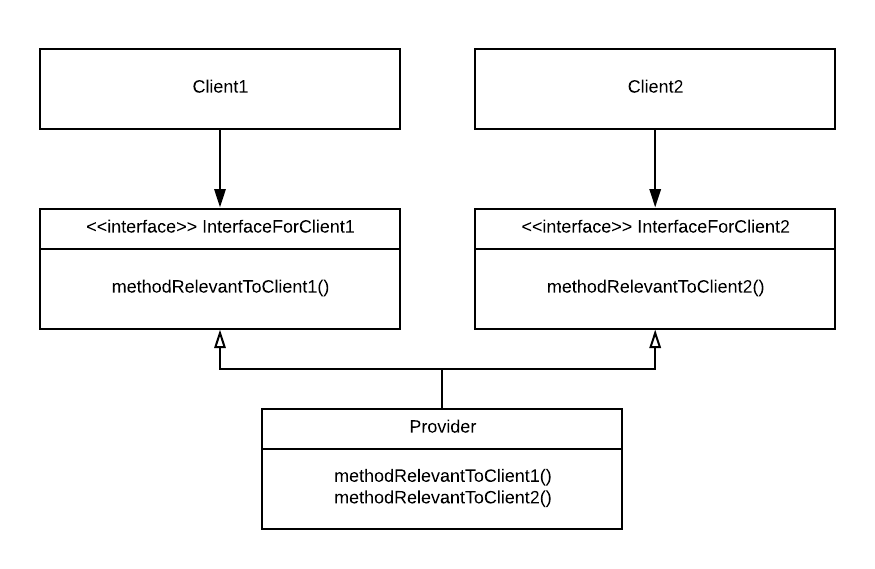

We can prevent that by making Provider implement two interfaces, each relevant to a particular client.

An alternative, more general formulation of the interface segregation principle would be “avoid depending on things you don’t need”. Importing a huge flexible third-party library could be suboptimal if all you’ll be using it for is some very small part of its functionality. For example, you may have to wait longer for bugfixes in the part you use because corresponding changes need to be made in other parts as wel. Careful consideration becomes even more important when the dependency you are considering also has dependencies of its own. People using Node.js may be familiar with the situation where you need to update a module you use because of a vulnerability discovered in some module that it indirectly depends on, three levels down the dependency chain, for some functionality you don’t care about.

Dependency inversion principle

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

A more relaxed formulation would be this:

- Specific parts of your system should depend on general parts, not the other way around.

- Abstraction can be used as a technique to reverse the direction of dependencies if needed.

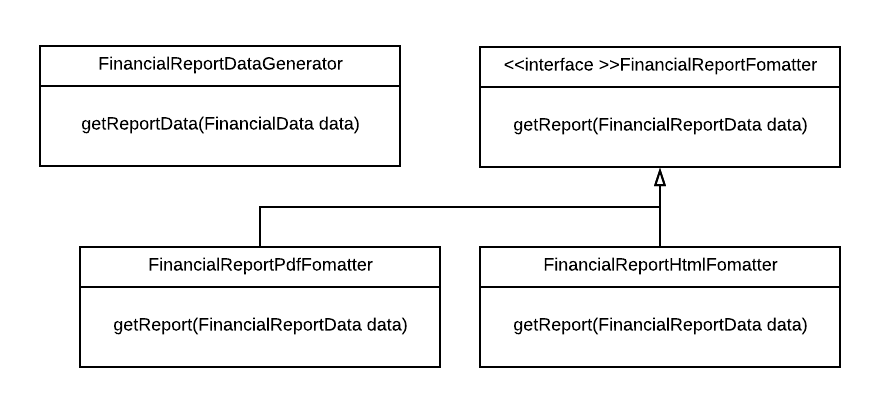

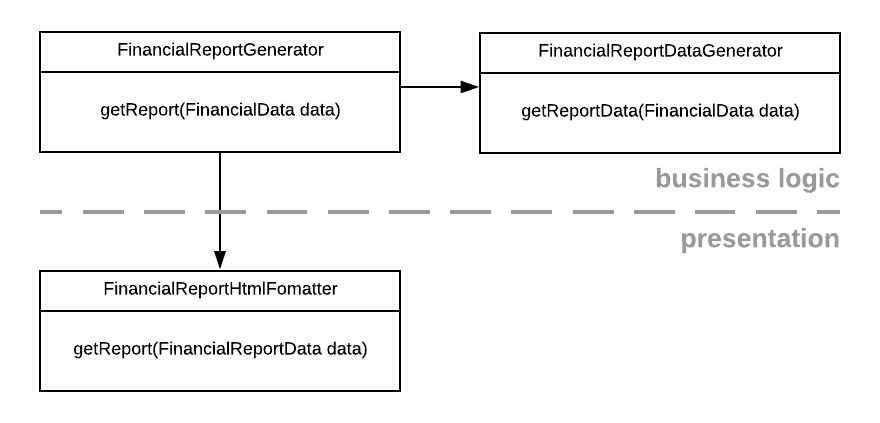

As an example, let’s go back to our financial report again. Let’s say we split out the logic for generating the data for the report and the logic for formatting it into HTML.

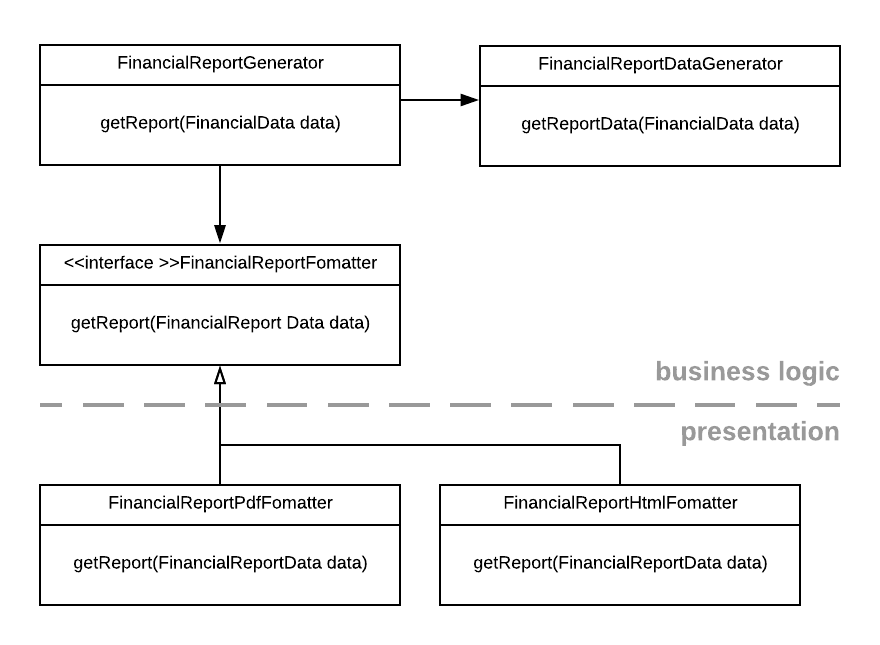

While there is a clear separation of responsibilities, we see that FinancialReportGenerator (a general class which we could consider part of the application’s business logic) depends on FinancialReportHtmlFormatter (a specific class formatting the report in a specific format). In order to turn this around, we can introduce the FinancialReportFormatter abstraction which we also saw in the section on the open-closed principle.

Now, FinancialReportGenerator depends on an abstraction (which could be considered part of the business logic), and specific formatters depend on that abstraction. By doing this, we have reversed the direction of dependency across the boundary between business logic and presentation. While the flow of control stays the same (the business logic will invoke a specific formatter), the dependency points in the other direction.

Note that the same abstraction mechanism has now also allowed us to easily extend our program with different formats (see open-closed principle).

Because we don’t want the general FinancialReportGenerator to depend on specific formatter classes, we also don’t allow FinancialReportGenerator to instantiate these classes. Instead, we can use dependency injection to pass a specific formatter instance to FinancialReportGenerator, while FinancialReportGenerator itself doesn’t have to care which specific class it receives an instance of (Liskov substitution principle!). In cases where instantiation of specific classes needs to be triggered by the general class, we could instead pass a factory object to the general class. The general class depends on a general interface or abstract class describing what such a factory object looks like, while the specific factory object that the general class receives determines the exact type of specific classes that will be created.

Finally, let’s have a look at the the Observer pattern. The Observer pattern allows general classes to trigger methods on specific classes by letting the specific classes subscribe to the general class. When using this pattern, the general class does not know about the specific classes. All it knows about is an Observer interface that the specific classes implement. In essence, this is just another manifestation of the dependency inversion principle.