Branch By Abstraction and application strangulation

- The basic idea

- Anatomy of the abstraction layer

- Why not real branches?

- Application strangulation

- A real-world strangulation example

- Resources

Branch By Abstraction is a development technique that allows teams to make large changes while collaborating in a single branch and without breaking the system while the change is in progress. It is an alternative to long-lived feature branches. This post will also talk about application strangulation, which is a similar technique that works at a higher level.

The basic idea

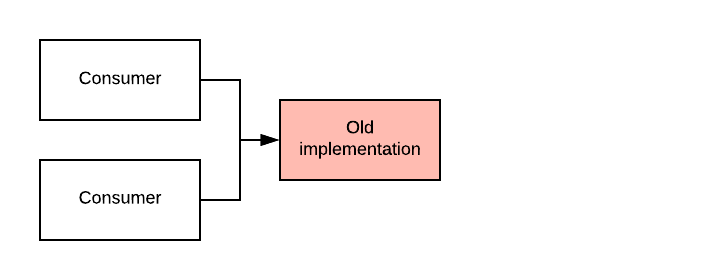

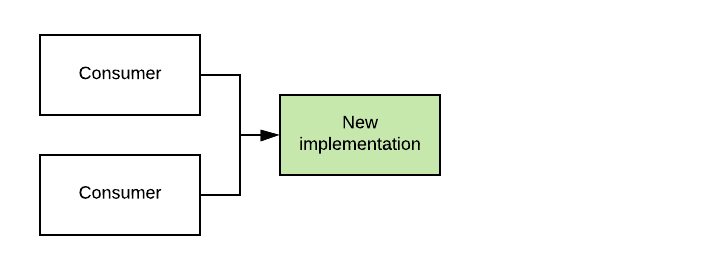

The basic idea behind Branch By Abstraction is simple. Let’s say we have some component in our system that a number of consumers depend on. Now, we want to replace our implementation of that component by a new implementation. We are also assuming that the change is so big that it requires more than a few days of work and doesn’t fit inside a single commit.

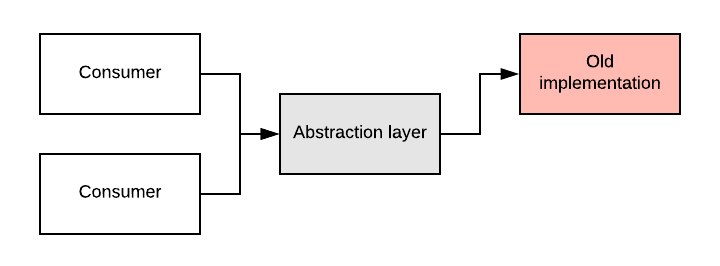

Our first step is to create an abstraction layer on top of the old implementation. Then, we refactor the consumers so they now call the old implementation through the abstraction layer. This could potentially happen in multiple commits, all while keeping the system working.

Depending on the case, it could also make sense to only move some consumer(s) to the abstraction layer, then follow the rest of these steps, and then go on to the next consumer.

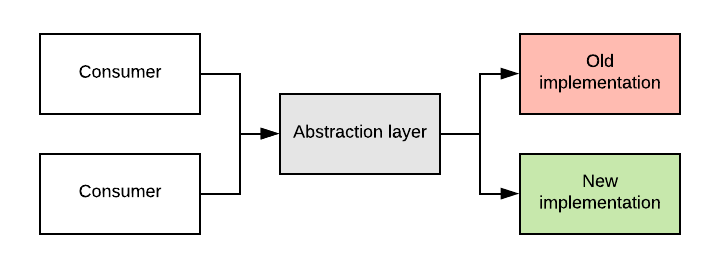

Now, we can start creating the new implementation, still sitting behind the abstraction layer. We do this in multiple, relatively small commits. We use the abstraction layer as a way to control the extent to which consumers will be using the old or new implementation. This way, we can gradually move consumers onto the new implementation while still committing regularly and keeping the system working.

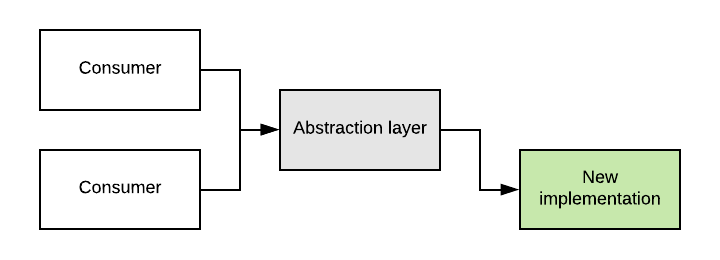

At some point, we will find that nothing is using the old implementation anymore, which means we can safely delete it.

We could choose to delete the abstraction layer itself if that makes sense.

Anatomy of the abstraction layer

The abstraction layer could simply be an interface that both your old and new implementation will implement. This allows you to choose which of the implementations (old or new) to instantiate when a consumer requires an object conforming to that interface.

It’s also possible for the abstraction layer to be an actual class that delegates to the old or new implementation as needed. This could be based on some flag (built into the code or in a configuration file) that allows developers working on the new implementation to test it while others are not affected by it yet. Alternatively, the abstraction could use the new implementation for some calls and the old implementation for others.

Another option is that the abstraction layer is an actual layer in your application’s architecture. For example, if you are moving to a new persistence framework and you are using a layered architecture, you could already have an abstraction layer in the form of repositories that encapsulate all interaction with the database. This could allow you to make the change one repository at a time, while repositories you didn’t touch are still using the old persistence framework.

Why not real branches?

The problem with using real version control branches for doing these kinds of changes is that merging the changes is almost guaranteed to be a huge pain. Making large changes means that your branch will probably touch a large part of the codebase. The fact that the changes are large also means you will probably spend a long time working on them, giving the rest of the team plenty of time to make changes to the parts of the codebase you touch in a way that conflicts with what you are doing.

It’s even worse if your team also uses long-lived branches for regular feature development, because that increases the chances that the rest of the team are making incompatible changes that you don’t know about until the team has already invested a lot of time in them.

With Branch By Abstraction, you don’t have these kinds of issues. You are making incremental changes that keep the system working and you regularly commit these changes into the single branch that your team collaborates on. This way, any potential conflicts will surface quickly and you don’t have to worry about colleagues making changes that will turn the step of finishing your migration into a living hell. For example, you could decide to pause the migration for a while in order to work on a new high-priority feature, without the fear that the rest of the team will use this pause to do work that conflicts with your migration work. Because the system is also working at all times, it is perfectly possible to release a new version of the system that already contains your partially-completed migration.

For a more detailed look at the reasons for avoiding long-term feature branches, have a look at my post on Trunk Based Development.

Application strangulation

Application strangulation is a technique that is very similar to Branch By Abstraction. The main difference between the two is that they operate at a different level. While Branch By Abstraction uses the abstraction mechanisms of your programming language, application strangulation could be used to migrate between different applications potentially written in completely different languages. When applying application strangulation, the abstraction layer typically comes in the form of a reverse proxy that decides whether to call the API of the old application or the API of the new application.

A real-world strangulation example

The article Bye bye Mongo, Hello Postgres describes how The Guardian used application strangulation to move from MongoDB to PostgreSQL, keeping their system working while performing the migration. MongoDB would stay their main source of truth until the migration was completed, but in the meantime they also needed to make sure that all of their data got migrated into PostgreSQL and that the system was able to run on PostgreSQL only once fully switched over.

Potentially, Branch By Abstraction could have been an option here. The abstraction layer would then have been a layer that abstracts access to the database and chooses to interact with MongoDB, PostgreSQL or potentially both. However, as there was very little separation of concerns in the original application, introducing that kind of abstraction layer would have been costly and risky. Therefore, the team decided to create a new application, with the same API as the old one, that would talk to PostgreSQL instead of MongoDB.

Once the new application was running next to the other one, the team created a reverse proxy that worked as follows:

- Accept incoming traffic

- Forward the traffic to the primary API and return the result to the caller

- Asynchronously forward the traffic to the secondary API

- Compare the results from both APIs and log any differences

After migrating the existing data, any differences between the results from both APIs would indicate bugs that needed to be solved. If the team got to the point where there were no differences being logged, they could be confident that the new API works in the same way as the old API. Switching the primary and secondary API in the proxy allowed the team to essentially switch to the new API while still having a fallback in the form of the old API that was still receiving all requests.

The migration of existing data itself also made use of the fact that both applications had the same API. The flow was as follows:

- Get content from the API backed by MongoDB

- Save that content to the API backed by PostgreSQL

- Get the content from the API backed by PostgreSQL

- Verify that the responses from (1) and (3) are identical

Finally, when everything was working with the new API as primary, the team got rid of the proxy and the old API in order to complete the migration.

Note that, during the period in which both APIs were running next to each other, calls for both reads and writes were being forwarded to each API and the results were compared. This is very similar to the Duplicate Writes and Dark Reads that we saw as part of the Expand-Contract database migration strategy in the post on Feature flags